As the majority of

Americans turned from activism to conservatism during the Reagan years,

[1]

the Guerrilla Girls emerged as a feminist art group who challenged sexism and

racism in the Western art world. Established in 1985, the Guerrilla Girls formed in reaction to an

exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City the year before.

[2]

The exhibition’s title, “An

International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture,” and catalogue provided

to museum visitors suggested that the featured works were those that best

encapsulated the past decade of painting and sculpture.

[3]

The Guerrilla Girls were propelled to

action by this exhibition for they felt it did not represent the international

art community. Instead, they

believed that the exhibition represented the exclusion of, and discrimination

against, women artists and artists of colour. Of the one hundred and sixty-nine artists selected for the

show, only thirteen of them were women and none were artists of colour.

[4]

This essay will explore a variety of

tactics used by the Guerilla Girls to expose the prevalence of sexist and

racist discrimination in art institutions and culture at large.

Since their inception in

1985, the Guerrilla Girls have successfully organized exhibit interventions,

art gallery protests, feminist lecture series, and provocative publications

through which they can express their platform of inclusion. They have studied

and drawn from lessons of past feminist movements, while developing their own

new and unique approach to feminist issues. Their decisions to maintain anonymity, to use humour and

irony, and to recognize the power of the media have been the foundation of

their success. The group’s inclusive vision and avoidance of militantly radical

activities has contributed to the positive reception of their ideas.

The Guerrilla Girls

remain current and culturally relevant. Looking to the feminist movements of

the past, especially the second-wave movement of the late 1960s and 1970s, the

Guerrilla Girls noticed tactical issues that could have been prevented with

anonymity. In A History of U.S.

Feminisms, author Rory Dicker notes that conflicts arose among women

involved in the second-wave movement when one woman or a small group of women

garnered greater media attention.

[5]

Dicker mentions that many second-wave

feminists preferred that all women activists had an opportunity for equal

representation and participation in the movement and media attention

surrounding it, and refers to Kate Millett, whose book Sexual Politics landed her on the cover of Time magazine.

[6]

Millett became the focal point of

public interest, and as a result, she was targeted by fellow feminists for

being attention-seeking and self-interested.

[7]

In order to avoid issues of

spotlighting that had plagued previous feminist movements, the Guerrilla Girls

decided to withhold their names and personal appearances. This allowed them to avoid problems of

personal grandstanding; if no names were revealed, all group members would

receive equal recognition and praise.

By choosing anonymity,

the Guerrilla Girls also succeeded in protecting themselves from potentially

harmful backlash.

[8]

Many of the founding members of the

Guerrilla Girls were artists, art critics, curators, and museum administrators,

and they were targeting some of the most important members and institutions of

the Western art world. As a result, they were potentially risking their careers

and livelihoods. The Guerrilla

Girls protected their personal interests by withholding their names and

appearing in public under the shield of gorilla masks. Consequently, they were allowed greater

liberty to say and do as they wanted without fear of reprisal.

The Guerrilla Girls recognized

this benefit, but cited their main reason for remaining anonymous as wanting to

keep the public focused on the issues they were addressing as opposed to the

individual personalities and appearances of the women presenting them.

[9]

Taking advantage of the anonymity

to put their anti-sexist, anti-racist platform into action, each member of the

Guerrilla Girls adopted the name and persona of an artist who the group felt

had not been afforded proper representation and recognition in the Western art world.

[10]

By adopting the names of women artists

and artists of colour who had been ignored, such as Alice Neel, Georgia

O’Keeffe, and Liubov Popova, the Guerrilla Girls brought attention to these

individuals. They prompted the

public to inquire about these artists, and to question why they have been

underrepresented in the history of art.

Although anonymity

provided the Guerrilla Girls with a variety of benefits, critics often cite

their decision to remain anonymous as one that is cowardly, dishonest, and unfair. However, these critics are often

individuals who the Guerrilla Girls have centered out as being sexist and

discriminatory.

[11]

For example, Leo Castelli and other

gallery owners, such as Allan Frumkin and Pat Hearn, were the targets of a

Guerrilla Girls’ poster entitled “These

Galleries Show No More than 10% Women Artists or None At All.”

[12]

Therefore, the gallery owners’

critiques of the Guerrilla Girls’ anonymity appear tainted by bias, and their

credibility is diminished. The Guerrilla Girls see their choice of remaining

anonymous as capitalizing on a strategy that has consistently been used to

oppress women. The Guerrilla Girls

highlight the important difference between chosen and enforced anonymity, and

suggest that because they embrace anonymity, they have prevented a patriarchal

art world and society from being able to use it against them. Mira Schor, writing for ArtForum magazine, recognizes that, “[w]hereas in the past anonymity had been a curse on

female artistic creativity, the Guerrilla Girls have embraced the strategic

benefits of their covert existences.”

[13]

In contrast to previous

feminist movements, which had adopted graver tones, the Guerrilla Girls

favoured a humorous approach. In a 1990 interview conducted for a retrospective

show of Guerrilla Girls work, group member “Louise the Poster Girl” explained,

“[m]aking demands are the tactics of the 70s and let’s face it, they didn’t

really work very well … we decided to try another way: humour, irony,

intimidation, and poking fun.”

[14]

The Guerrilla Girls infused their

stance against sexism and discrimination with humour, contradictions, and

juxtapositions that encouraged the public to pay attention to, and get involved

in, their cause. In this way they

avoided classification and dismissal as angry and humorless women with chips on

their shoulders.

[15]

By calling themselves

“girls,” the group reclaims a word that could be used against them as a term of

dismissal and eliminates the potential for their opposition to suggest that

they are simply incompetent little girls who are “not complete, mature, or

grown up.”

[16]

The word “girl” also presents a comical juxtaposition with the word

“guerrilla,” which is traditionally used in military discourse. The Guerrilla

Girls do in fact employ militant tactics, but not in the traditional

sense. They have reinvented

guerrilla militancy, “waging what they call a cultural warfare… where the main

ammunition is wit.”

[17]

The group’s public attire,

which incorporates gorilla masks, fishnets, and short skirts, illustrates the

kind of humourous juxtaposition that has attracted public interest and helped

them to create a unified front. The gorilla masks suggest an aggressivity normally associated with men,

while their clothing is hyper-feminine in style.

[18]

Lucy Irigaray notes that the Guerrilla

Girls’ decision to dress in an overtly feminine fashion allows them to “convert

a form of subordination into an affirmation, and thus begin to thwart it.”

[19]

In addition to their posters,

performances, and lectures, the Guerrilla Girls’ name and physical appearances

reveal their ability to use humour, irony, and juxtaposition as tools of

subversion and expression.

The Guerrilla Girls’

ironic and sarcastic tactics have also allowed them to fight discrimination in

the Western art world by highlighting contradictions within the museums,

galleries, and education facilities. For example, in 1988, they produced a poster entitled “The Advantages of being a Woman Artist” (Figure 1). This poster included

“advantages” such as “working without the pressure of success,” “being

reassured that whatever kind of art you make it will be labeled feminine,” and

“not having to be in shows with men.”

[20]

Instead of making demands, the Guerilla

Girls used sarcasm and irony to bring attention to the gender discrimination

prevalent in American art institutions. In doing so, the Guerrilla Girls highlighted incongruities in the art

world’s rhetoric, which ostensibly supported gender equality, by employing

satire as a method of critique.

[21]

When asked about their use of humour in

an online Question and Answer, the group responded, “[w]e've discovered that

ridicule and humiliation, backed up by irrefutable information, can disarm the

powers that be, put them on the spot, and force them to examine themselves.”

[22]

“The

Advantages of Being a Woman Artist” prompted the public to question why

women are being denied success, why women’s art is automatically labeled as

“feminine,” and why women’s art is not being exhibited alongside men’s

art. The Guerrilla Girls’ message

achieved international recognition as this poster was translated into more than

eight languages and circulated across the globe.

[23]

The Guerrilla Girls used this poster to

illustrate to the global art community the double standards that exist within

Western art world practices.

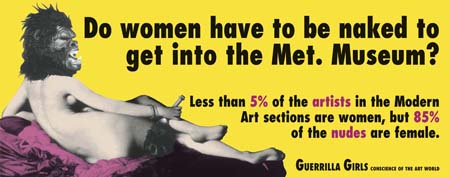

The Guerrilla Girls

gained iconic status with their 1989 poster entitled "Do Women have to be Naked to get into the Met. Museum?" that

incorporated both text and visual imagery to highlight their platform (Figure 2). The poster features a reclining nude reminiscent of Jean

Auguste Dominique Ingres’ Grand Odalisque (1814), wearing a gorilla mask, juxtaposed with statistics reflecting the bleak

representation of women artists in the Metropolitan Museum in New York

City. On the poster the Guerrilla

Girls state that “[l]ess than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art Section are

women, but 85% of the nudes are female.”

[24]

By appropriating Ingres’ work, the

Guerrilla Girls have ironically paired an iconic symbol of patriarchal art with

a statistic in order to challenge gender discrimination in the art world.

[25]

These “believe it or not” statistics

underscore the gap that exists between ideal social structures and actual

practices, and make denial or indifference inappropriate reactions to

discrimination.

[26]

In contrast with

previous feminist groups who had, at times, engaged in hostile relationships

with the media, the Guerrilla Girls recognized the importance of the media as

an effective means of establishing a positive rapport with the public.

[27]

Professor Christine Tulley comments on

this relationship, and suggests that without spectacles that attract media

attention, the Guerrilla Girls’ mandate “may not be heard or, if heard, may

quickly fade from public interest.”

[28]

Tulley

notes that it is the Guerrilla Girls’ recognition of the media’s authority that

has allowed them to outlast other feminist groups such as the Women’s Action

Coalition.

[29]

The Guerrilla Girl’s affiliation with

the media enables them to reach out to a more diverse audience.

Another reason the

Guerrilla Girls have remained current and effective over the past twenty-five

years is related to their critical examination of past feminist groups and

desire to avoid the stigmatized persona of the “angry feminist.” The Guerrilla Girls do not aim to

completely destroy Western art institutions nor do they want to totally

reinvent society; instead, they promote change within these frameworks. According to Anne Teresa Demo, the

Guerrilla Girls’ posters, lectures, and performances employ strategies of

“demystification rather than revolution.”

[30]

The Guerrilla Girls avoid public

alienation by advocating change within the museums, galleries, and Western art

canon as opposed to calling for a complete eradication of these

institutions. Advocating for the

latter would likely lead the public to label them as radicals, and therefore

their platform would be considered both impractical and unrealistic.

The Guerrilla Girls’

1998 publication, The

Guerrilla Girls’ Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art, is an

example of how the group highlights sexism and discrimination. With this publication, the Guerrilla

Girls chose to work within the established framework with what Cynthia Freeland

has called the “add women and stir” approach.

[31]

Similar to their use of past artists as

personas in the public eye, The Guerrilla Girls’ Bedside Companion to the

History of Western Art underscores the void of women artists and artists of

colour within traditional discourse. The introductory pages prompt the viewer to consider the following

question: “Why haven’t more women

been considered great artists throughout Western history?”

[32]

The Guerrilla Girls have faced criticism for implementing this “add women and

stir” approach, as some radical feminist groups feel that the entire Western

art discourse should be reinterpreted and reinvented. Although a complete revision of the Western art canon may be

the ideal way to achieve equality for underrepresented artists, the Guerrilla

Girls recognized that this approach was not realistic. Adopting it would likely alienate or

intimidate potential supporters and this could inhibit their success. Instead the Guerrilla Girls ask the

reader to question why they have previously been ignored.

A considerable

difference between the Guerrilla Girls and the second-wave feminists is that

the Guerrilla Girls consistently place a great emphasis on inclusiveness. Throughout their twenty-five year

existence, the Guerrilla Girls have worked to eliminate divisions between

feminists and non-feminists, as well as divisions among the feminists

themselves. Chicana feminists Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa influenced the

Guerrilla Girls’ inclusive approach to feminism. In 1979, Moraga and Anzaldúa declared, “[w]e want to express

to all women – especially white middle-class women – the experiences

which divide us as feminists; we want to examine incidents of intolerance,

prejudice, and denial of difference within the feminist movement.”

[33]

Similarly, the

Guerrilla Girls have worked to include all ethnicities, ages, economic levels,

and sexual orientations.

[34]

This strive

for inclusiveness parallels a larger aim of the third-wave feminist movement of

the 1980s and 1990s: diversity in membership and advocacy. The Guerrilla Girls advocate for

diversity by using masks to conceal identifiable physical traits such as skin

colour or age. In fact, even the

gorilla masks, which many claim subvert the group’s aim of diversity, are all

different. While one member may

wear a mask that is covered in hair and shows an intimidating tooth-bearing

grin, another may sport a hairless mask with a tight-lipped smile and flaring

nostrils. Through supporting and

encouraging diversity, the Guerrilla Girls have increased in numbers; instead

of attracting solely white middle-class heterosexual women, the group now appeals

to a far greater number of Americans. Also, the inclusive approach legitimizes the Guerrilla Girls, for if

they were an exclusive group, their challenges against discrimination, sexism

and racism would seem contradictory.

The group also

advocates for change outside of the art world, and over the years has expanded

their projects to include gay and lesbian rights, homelessness, and politics.

For instance, in order to highlight the dire situation of homeless Americans,

the Guerrilla Girls created a poster to

reveal that a prisoner of war is afforded more rights than a homeless

person. They state that

under the Geneva Convention, a prisoner of war is entitled to the food,

shelter, and medical care that many homeless Americans struggle to attain.

[35]

Through championing other causes, the

Guerilla Girls are able to increase their support base, and in turn, their

success. The Guerrilla Girls have expanded their presence in the public sphere

by commenting on a wide range of social injustices and demonstrating that their

advocacy is not limited to the art world. As the June 1990 New York Times article included in their

retrospective show “Guerrilla Girls Talk Back” reveals, “the Guerilla Girls are

not art critics, they’re social critics.”

[36]

Art critic, writer, and

theorist Lucy R. Lippard regarded the Guerrilla Girls as having “almost

single-handedly kept women’s art activism alive” from their inception in 1985

through to the mid 1990s.

[37]

Similarly, early on in their career,

the Guerrilla Girls were recognized by New York magazine as one of the

four powers to watch for in the art world.

[38]

Maintaining their anonymity, inclusivity, satirical humour, social activism and

media-friendly stance, the Guerilla Girls have managed to stay relevant and

promote an anti-discriminatory agenda in the art world and elsewhere. In recognition of this, the Guerrilla

Girls were asked in 2009 to create a poster to

commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the shootings that took place at École

Polytechnique in Montreal, Canada. The group, now well established in social activist discourse, explored

the continuation of hate speech against women and feminism by quoting

historical figures such as Confucius, Frank Sinatra, Rush Limbaugh, and Pablo

Picasso.

[39]

Gloria Steinem, second-wave feminist

and key leader of the Women’s Liberation Movement, sums up the nature of the

Guerrilla Girls’ success:

Their very anonymity makes clear that

they are fighting for women as a caste, but their message celebrates each

woman's uniqueness. By insisting

on a world as if women mattered, and also the joy of getting there, the

Guerrilla Girls pass the ultimate test: they make us both laugh and fight; both

happy and strong.

[40]

Building on their early successes filling the streets

of New York City with posters that highlighted gender and racial discrimination

in the Western art world, the Guerrilla Girls have developed into a powerful

collective that continues to further activist discourse and social change.

BIBLIOGRPAHY

Boyer, Paul S. et al. The Enduring Vision: A History of American

People. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2006.

Broude, Norma and Mary

D. Garrad, eds. The Power of Feminist

Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact. New York:

Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers, 1994.

Dicker, Rory. A History of U.S. Feminisms. Berkeley,

California: Seal Press, 2008.

Falkirk Cultural

Center. Guerrilla Girls Talk Back: The

First Five Years. San Rafael, California: Falkirk Cultural Center, 1991.

Freeland, Cynthia. But is it art? An Introduction to Art Theory.

New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Guerrilla Girls. Montreal Project: Disturbing the Peace.

2009.

–––––. Online:

Frequently Asked Questions. 2006.

http://www.guerrillagirls.interview/faq.shtml.

–––––. Online:

Website Blurbs. 2006.

http://www.guerrillagirls.com/info/blurbs.shtml.

–––––. Guerrilla

Girls’ Beside Companion to the History of Western Art. New York: Penguin

Group Publishers, 1998.

–––––. The

Advantages of Being a Woman Artist. 1998.

–––––. What’s

the Difference between a prisoner of war and a homeless person? 1991.

–––––. Do

women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum? 1989.

–––––. The

Galleries Show No More than 10% Women Artists or None At All. 1985.

Lippard, Lucy R. The Pink Glass Swan: Selected Feminist Essay

on Art. New York: The New Press, 1995.

Lustig, Suzanne. “How

and why did they Guerrilla Girls alter the Art World Establishment in New York

City, 1985-1995?” Women and Social

Movements in the United States 1600-2000. Spring 2002.

http://womhist.alexanderstreet.com/ggirls/intro.htm

McShine, Kynaston. An International Survey of Recent Painting

and Sculpture. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1984.

Olsen, Lester C. et al,

eds. Visual Rhetoric: A Reader in

Communication and American Culture. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage

Publication, Inc., 2008.

Schor, Mira. “Girls

will be Girls.” ArtForum (September

1990).

Tulley, Christine.

“Image Events Guerrilla Girl Style: A 20-Year Retrospective.” Enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric,

Writing, and Culture. 6.2 (Spring 2009).

NOTES

[1]

Paul S. Boyer et al., The

Enduring Vision: A History of American People (Boston, New York: Houghton

Mifflin Company, 2006), 666-667.

[2]

Falkirk Cultural Center, Guerrilla

Girls Talk Back: The First Five Years (San Rafael, California: Falkirk

Cultural Center, 1991), Interview.

[3]

Kynaston McShine, An

International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture (New York: The Museum

of Modern Art, 1984), 11.

[4]

Falkirk Cultural Center, Guerrilla

Girls Talk Back, Interview.

[5]

Rory Dicker, A History

of U.S. Feminisms (Berkeley, California: Seal Press,2008), 85.

[8]

Norma Broude and Mary D.

Garrad, eds., The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s,

History and Impact (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, 1994), 99.

[9]

Falkirk Cultural Center, Guerrilla

Girls Talk Back, Interview.

[10]

Lester C. Olson et al.,

eds., Visual Rhetoric: A Reader in Communication and American Culture (Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc., 2008), 202.

[11]

Mira Schor, “Girls will be

Girls,” Art Forum (September 1990), 125.

[12]

Guerrilla Girls, The

Galleries Show No More than 10% Women or None At All, (1985).

[14]

Falkirk Cultural Center, Guerrilla

Girls Talk Back, Interview.

[15]

Cynthia Freeland, But is

it art? An Introduction to Art Theory (New York: Oxford University Press,

2002), 123.

[16]

Olson et al., eds., Visual

Rhetoric, 246.

[18]

Olson et al., eds., Visual

Rhetoric, 246.

[20]

Guerrilla Girls, The

Advantages of Being a Woman Artist, (1988).

[21]

Olson et al., eds., Visual

Rhetoric, 242.

[23]

Olson et al., eds., Visual

Rhetoric, 241.

[24]

Guerrilla Girls, Do

Women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum? (1989).

[25]

Olson et al., eds., Visual

Rhetoric, 249.

[27]

Christine Tulley, “Image

Events Guerrilla Girl Style: A 20-Year Retrospective,” Enculturation: A

Journal of Rhetoric, Writing and Culture (Issue 6.2, Spring 2009), 2.

[30]

Olson et al., eds., Visual

Rhetoric, 201.

[32]

Guerrilla Girls, The

Guerrilla Girls’ Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art (New York:

Penguin Group Publishers, 1998), 7.

[35]

Guerrilla Girls, What’s

the Difference between a prisoner of war and a homeless person? (1991).

[36]

Falkirk Cultural Center, Guerrilla

Girls Talk Back, Interview.

[37]

Lucy Lippard, The Pink

Glass Swan: Selected Feminist Essays on Art (New York: The New Press,

1995), 257.

[39]

Guerrilla Girls, Montreal

Project: Disturbing the Peace (2009).