Munro Connections

Western alumni Isobel Raven shares her childhood memories of Alice Munro.

ROOTS

In the early 1930’s, two girls were born in Huron County in rural south-western Ontario. They lived on farms separated by about twenty miles of mildly hilly ground, some of it prosperous farmland and some, unwisely wrested from the forest generations ago, overgrown with thorn and chokecherry. The best farms had a stand of maple forest at the back; the worst had a cedar swamp. The sleepy Maitland River and its tributaries drain this unremarkable terrain.

They walked under leafy maples and perhaps a spreading elm to one-room schools that had pictures of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth above the blackboard, flanked by the Union Jack and the Ontario Ensign. Every school day began with the singing of God save the King, the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer, and a Bible reading. The older girl moved on to the town school in Wingham, but those features of the school day were still the same.

Their parents did not worry about their happiness. They wanted their daughters to be good, and a credit to the family. Respect within the community and the extended family were to be carefully maintained, and the children’s public behaviour had to be impeccable.

Both girls were largely solitary and found their companionship in books. One wrote stories obsessively; the other didn’t write much more than what her teachers required. But she played a summer game with her sister where they wrote up imagined newspaper pieces: each other’s weddings and obituaries.

The girls were quite unknown to each other, and have only twice been in the same room together, but a connection was formed which has endured for a long time and has been significant in the life of Isobel, the younger of the two.

When Isobel Dennis, a pimpled Grade 11 student stood in the dusty front hall of her new (to her) school in 1950,she inspected a row of oak shields that had until recently been awarded to worthy students of Wingham High School. They were no longer in use. Through a process of amalgamation that swallowed up all the small local high the schools, the school had become Wingham District High School. Isobel’s continuation school at Brussels had been a victim.

She noted with jealousy that one Alice Laidlaw had won the shield for proficiency in English five consecutive years. Jealousy, because she thought that if the shield were still being awarded, she might win it herself.

Though Alice had graduated a year earlier, her name still hung in the air, mentioned with something like awe. Alice was a hard act to follow, but Isobel tried. Though she didn’t want the labels “smart” or “genius” (uttered with a faint sneer), high marks were her only source of glory, athletics, student government, and social success being quite out of her range.

The world knows that Alice Laidlaw became Alice Munro, acclaimed story writer, winner of a long list of awards, and finally, in 2013, the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Isobel Dennis, became Isobel Raven, an undistinguished teacher and obscure writer of a couple of self-published books.

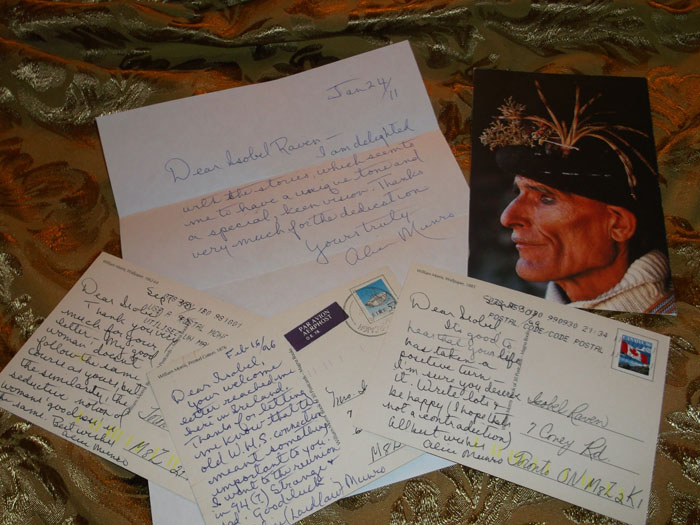

The connection, initiated by me, Isobel, in 1996, took the form of a letter to Alice, telling her of my longstanding interest in her career and ridiculous feeling that it somehow was a credit to me because of my early attention to her accomplishment. I included a stamped self-addressed postcard as an incentive for reply. Alice did indeed send back my postcard with a note and her signature.

Other letters with postcards followed in 1998 and 99. In 2001, after she published Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Love, Marriage, the letter to Alice didn’t include the stamped postcard, because, I said, I thought she could now afford a stamp. Alice replied that indeed she could and sent at her own expense a card with a portrait of a sad-eyed comic. By now I was telling her of my efforts to write, and she was kindly encouraging.

I was present at two events in Toronto where she read, but circumstances didn’t allow me to make myself known to her. Besides, I feared that I would make some kind of gushingly countrified gaffe.

When I dedicated A Flower for Allie, my own collection of short stories, to Alice Munro and sent her a copy of the book, Alice replied with a note expressing her thanks and delight with the stories. A treasured addition to my store of postcards.

As Alice Munro has done, I return in my thoughts to that shared landscape and the seemingly narrow society it supported. I see how it is both something to escape and something to treasure. I read Alice Munro with a sense of coming home. Her people are people I know. They go along living humdrum lives, and then they do something surprising. And I see that yes, they had it in them all the time.