Paradise Lost

Western professor uses his own visual impairment to help students connect with a blind poet

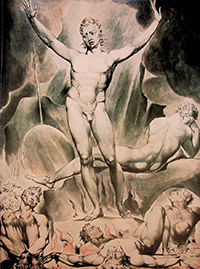

Satan summoning his legions

John Milton was totally blind when he composed his great biblical epic, Paradise Lost. He completed the poem in 1665 in a quiet Buckinghamshire village, where he had sought refuge from the Great Plague, then raging in London. John Leonard, who has taught Milton courses at Western for almost forty years, recently had his own brush with blindness. Leonard’s eyesight, which has been poor his whole life, began to fail in 2020, just as Covid struck. The pandemic prevented him from getting the medical help he needed, and for ten months he was almost blind.

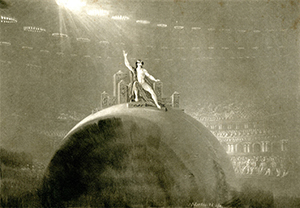

Satan enthroned in Pandemonium

Unable to read books, he could not engage in traditional scholarship, but he could still engage with Milton. Leonard knows much of Paradise Lost by heart and his students have for years exhorted him to record himself reading the poem. In the darkest months of 2020 and 2021, during lockdown, he did just that. His son, Alexander Leonard, a media professional, recorded him reading the entire poem aloud, partly from memory, partly prompted by a large screen in dark mode. Two operations have since restored Leonard’s distance vision, and for the past year he has applied himself to the next stage of the project – the addition of visual images from illustrated editions of Paradise Lost in the Weldon Library’s G. William Stuart Collection of Milton and Miltoniana – one of the best Milton collections in the world.

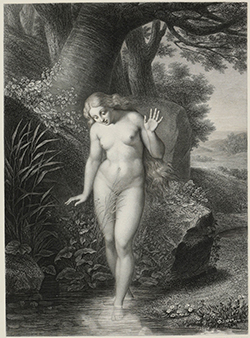

Satan about to possess the Serpent

Paradise Lost has the reputation of being a difficult text, and it does look intimidating on the page. But years in the classroom have taught Leonard that the poem’s long, breathy sentences can be clearly understood when read aloud. Some excellent audio recordings are commercially available, but Leonard’s video recording will be posted online as a free educational resource, hosted by Western and available to users everywhere. Visuals are an important part of the project. T. S. Eliot faulted Milton for having no visual imagination, because he was blind. Leonard has long resisted Eliot’s criticism in his scholarship, now he plans to challenge it in a more direct way. “No visual imagination?” he exclaims, incredulously. “Milton has inspired more visual artists than any other English poet. J. M. W. Turner, William Blake, Henry Fuseli, John Martin, Gustave Doré. . . .” Leonard’s project uses illustrations by all these and many other artists, placing them in a sequence that follows the poem’s narrative arc. Leonard is much indebted to his colleagues in the Archives and Special Collections, Western Libraries. “I could not have done this part of the project without the generous support of Deborah Meert-Williston, JoAnne Paterson, Arielle Vanderschans, and co-op student Yeliz Baloglu Cengay. They helped me jump through the technical and legal hurdles and did the hands-on work of producing high-quality digital images with Weldon’s state-of-the-art scanning equipment.”

Eve encounters her own reflection

Illustrated editions are not the only visual resource Leonard uses. "Paradise Lost contains many epic similes and allusions to the Bible and classical mythology,” he explains. “These stories have been depicted in many paintings, some famous, some less so, but all now available digitally in the public domain. When Milton alludes to tales and legends such as the Tower of Babel or the abduction of Persephone, I display paintings by artists such as Pieter Breugel or Cecco Bravo to add immersion.” Leonard also uses more modern images. “Paradise Lost is not just an epic,” he explains, “it is also a great work of science fiction. Milton’s Satan is the most intrepid space traveller in all of literature. Milton even coined the modern astronomical sense of the word ‘space’ in Paradise Lost."

Satan arrives at the earth

Leonard conveys this aspect of the poem by using NASA images of deep space taken by the Hubble and Webb telescopes. He also uses the classic photographs “Earthrise” and “the pale blue dot” for the dramatic moment when Satan homes in on our tiny blue-green planet. For the poem’s more fantastical and otherworldly locations – heaven, hell, chaos, and the exoplanets that Satan briefly passes on his interstellar journey -- Leonard has created his own images using AI technology. He is currently about halfway through the visual part of the project. Once complete, the video recording will include approximately 1,600 visual images, which will be displayed for roughly half of the 12-hour reading.

Photo: Western Communications

“My goal,” Leonard explains, “is to bring Paradise Lost to as wide an audience as possible, not just here at Western, but to students across the globe – and not just students. The visual images are included to add immersion and excitement, like the visuals in a computer game. I have myself been a gamer for decades, even before the first Baldur’s Gate, so I have a sense of what works on a computer screen. Ten years before he lost his sight, Milton voiced his ambition to ‘leave something so written to aftertimes, as they should not willingly let it die.’ I have devoted my long career at Western to bringing Milton alive in the classroom. Since facing my own visual challenges, I want to bring Paradise Lost to a larger audience.” Leonard plans to launch the complete video recording in the spring of 2025.

View the Paradise Lost recordings:

Read more information on the Milton Collection at Western Libraries: https://westernlibrsc.github.io/MiltonatWestern/